The Profligacy of Photography and the Reinvented Universe

Why are there so many billions of photographs being produced today? Is it because they cost almost nothing to make? Or because they are so easy to make? Or is it because by photographing we think that we take ourselves outside of our own lives for a moment, becoming privileged witnesses? Or do we make so many photographs, and star in them, because we are convinced that appearing as image is somehow more important, and more enduring, than simply living our lives?

And why do we not similarly concern ourselves with the enormous number of words being uttered? Are there too many words? Not enough? Are they the “right” words?

Words, of course, can be ignored—the letters that populate them are abstract signifiers that must be deciphered, not as immediately referential as photographs. (And, fortunately, words are articulated in languages that many do not understand—photographs are thought to be universally and, for the most part, immediately understood, although this is a serious fallacy.)

Words are associated with issues of syntax and of context—how are words put together, in which sequence? It is not that someone has chosen the word “apple,” but that it is used to characterize someone as “the apple of my eye” rather than referring to one’s lunch finishing with “apple sauce.” We certainly do not give the same thought to photographic syntax and context—when media literacy is taught, it is almost always about words.

We all know the famous quotation, “If I had more time I would have written a shorter letter.” Why don’t we say the same of photographs—“If I had more time I would have made fewer photographs”?

Photographs are thought to demand less attention. We scan them quickly, treating them as a fast food in the world of online culture (many are now even produced to disappear in seconds). They take little time for the one wielding the camera to compose, and can be published and distributed immediately. Pointing the lens, all that their authors require is the visible, no longer the momentous. Everything has become fodder for the camera, including, quite frequently, the most trivial.

But such digitally-derived imagery may have met its match in digitally-derived words—not just any words, but those generated by computers. Recently, in a Google experiment, computers have taught themselves to “read” and caption photographs. Finally, the emperor, as it were, may be seen as having no clothes—“An apparently bored, thin boy with glasses sits behind a plate filled with breakfast items surrounded by people of a similar age known to him as his friends,” or “Yet another cat somersaults in the air.” There is something to the impersonal and matter of fact, although of course such captioning will be undoubtedly “personalized” in the near future (with perhaps a button allowing for the “user’s” predilection for more animated adjectives).

There is also enormous poetic potential here. My favorite of the captioned photographs released so far is the one, captioned by a human as “A green monster kite soaring in a sunny sky,” that was captioned quite differently by the computer: “A man flying through the air while riding a snowboard.” Somehow the software seems to have more surreal, Chagall-like points of reference.

What then would happen if computers re-captioned the entire history of photography? Not only what would the computer perceive, but also what information might it add? For example, would it further contextualize a sensuous Edward Weston nude to let the reader know that it was made at the same time that the Spanish Civil War was going on, and that Fascism would win? Or might it caption the famous photograph by Nick Ut of a young, nude Vietnamese girl, Kim Phuc, her skin burning from napalm, and include the various ways in which the publication of that image profoundly changed her life? Or, more broadly, might the computer, equipped with face-recognition software, help to finally write a history of photography from the points of view of the subjects of all of these famous photographs, not just the image-makers themselves?

We can then ask again why are so many photographs being produced ? No one would argue that we are more photogenic today, more exotic, more distinguished. Some would argue, on the other hand, that we are more needy, less assured of our own importance, or increasingly unable to grasp our roles as part of a larger cycle of life. Or perhaps, as Andy Warhol suggested, we are all seeking our own fifteen minutes of fame (at a shutter release of 1/100 of a second, it would take 90,000 pictures to cover our fifteen minutes of fleeting celebrity—an idiosyncratic way to justify our addiction to a voluminous photography).

Undoubtedly, if we stopped photographing (or, more importantly, stopped so frequently looking for situations to photograph) we could allow ourselves to look more intently inside of ourselves and to reflect upon our existential situations; to avoid doing just that may be another reason why we photograph so much. What, for example, might have happened to Meursault and his questioning stance in Camus’ The Stranger if he was carrying a “smartphone” (and not a gun)? Or to Holden Caulfield and his growing pains in Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye? Would they have tried to photograph away their distress? Or text the minutiae of their lives? More broadly, is it possible today to have a deeply introspective life while feeling pressured to supply one’s Facebook and Twitter followers with new material?

This explosive use of digital media is also indicative of something much deeper in our culture and in ourselves than the number of photographs or words produced. The invention of code-based media in the same era that we re-conceptualized ourselves as code, via DNA, is certainly no accident. And, like other media inventions before, as a civilization we are asking for a revolution that far transcends any specific use of digital media.

For example, when the printing press was invented, it allowed us to eventually evolve into nation-states, and for the Protestant Reformation to occur (no more quill pens and manuscripts in the hands of a small, secretive elite, etc.). The importance was not just in what was printed, but in the various political and social movements that emerged in its wake. The transformations that followed Gutenberg’s invention, including a more widespread literacy and easier access to various kinds of knowledge, can be seen as prefiguring our contemporary social media revolution.

Digital media take us much farther. The architecture of digital photography, for example, represents a conceptual leap transitioning from a concentration on appearance (phenotype) to the underlying code and related processes (genotype), in which the metadata increasingly vies with the image for importance (from a largely commercial angle, look at Getty Images’ recent decision to release 35 million photographs for free use, while asserting that their metadata is more valuable to advertisers). Digital, code-based media is a key driver in the re-conceptualization of humans and other living things as expressions of their genes.

As part of this re-conceptualization, seeds and the ways in which they can grow algorithmically can be viewed as more valuable than their manifestations. (One horrific example was the killing of a healthy, crowd-pleasing young giraffe named Marius in a Copenhagen zoo last year because its genes were thought by authorities to be already well-represented). Or, as artist Brian Eno suggested twenty-five years ago, referring to his own music as essentially an algorithm that is capable of forever transforming, even beyond his death: “Say you like Brahms and Brian Eno. You could get the two of them to collaborate on something, see what happens if you allowed them to hybridize. The possibilities for this are fabulous.”

Digital media then bring us to membership in a larger coded universe that manifests itself in a variety of ways—biological, social, political, spiritual, philosophical. We become part of a myriad of relationships based upon codes (sexual, ethical, quantum, religious, etc.) that are contemporary and also trans-national and trans-species, while negotiating a variety of passages between human and machine. (This is where the cyborg comes in, a status that many of us have already attained in, among things, our marriage to our smartphones.) In this shift, past and future are allowed to conflate as we simultaneously recognize within our coded selves both our ancestors and our progeny. One day digital media will be recognized for helping to bring us to this other place.

And, conceptually, we can also recognize another, related shift, provoked in part by digital media, from a Newtonian to a quantum worldview. The digital revolution has us moving from the reassuring continuity of analog media, largely anchored by a cause-and-effect Newtonian universe (aided by the printing press), to a more volatile quantum worldview of digital media with its discontinuities and non-linearities (hypertext), based upon an infrastructure of discrete integers and pixels that echo the quantum infrastructure powered by discrete, discontinuous packets of energy. The quantum emphasis on probabilities, the ambiguous superpositions of states (light as both wave and particle, for example, until it is observed), and the intermingling of distant forces, among other factors, will find a more welcoming environment in the digital.

Might we progress to a quantum government, or a quantum economy—and if so, what would they be? Could voting, as well as releasing the camera’s shutter, be viewed as the quantum collapse of multiple states? In this emerging universe will the photograph be able to mutate? Might it combine with other images and produce offspring? Or with musical algorithms and our own DNA? Or with distant particles spinning somewhere in the cosmos?

Much of this emerging worldview can be traced to photographs—discrete rectangles that foreshadowed the discrete digital, fragmenting the universe so that it became something less continuous, less the result of cause and effect, and more mysterious. It is not what is depicted within each photograph that matters in this transformation, but the ways in which photography functions. As Susan Sontag put it in 1977, “The camera makes reality atomic, manageable, and opaque. It is a view of the world which denies interconnectedness, continuity, but which confers on each moment the character of a mystery.”

So, to return once again to the original question posed here, why do we have so many photographs? The answer is actually quite simple: so that our world can be reinvented. Coded now so as to be able to link to each other and to all other digital media in diverse ways, to respond to events and to emotions, to parallel our DNA, to configure and reconfigure old and emerging conceptions of time and space, the photograph, which served to render our worldview as discrete and fragmented, now opens up new portals for re-conceptualization. And, one might suggest, this digital revolution may have occurred to allow us to re-discover, and re-invent, our universe as more holistic.

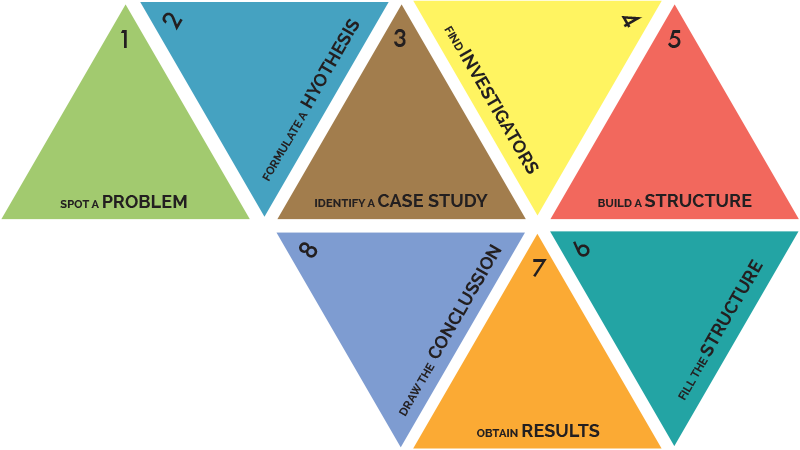

As we ready for the transition, “Octagon: A pocket manual for a systematic research tool,” conceived by an ethicist, image editor, and artist, helps to determine what of value we have already created, what is obfuscation, and what allows us to reflect more clearly. “Octagon” can be viewed as a response to Borges’ “Aleph,” the mystical tool that allowed one to see too much. And it helps to answer the pivotal question—as we are leaving one conceptual space, what is it that we want to take with us? What from our past will serve us well?

Copyright © 2015 Fred Ritchin